Sean Daniel

Technical Product Leader

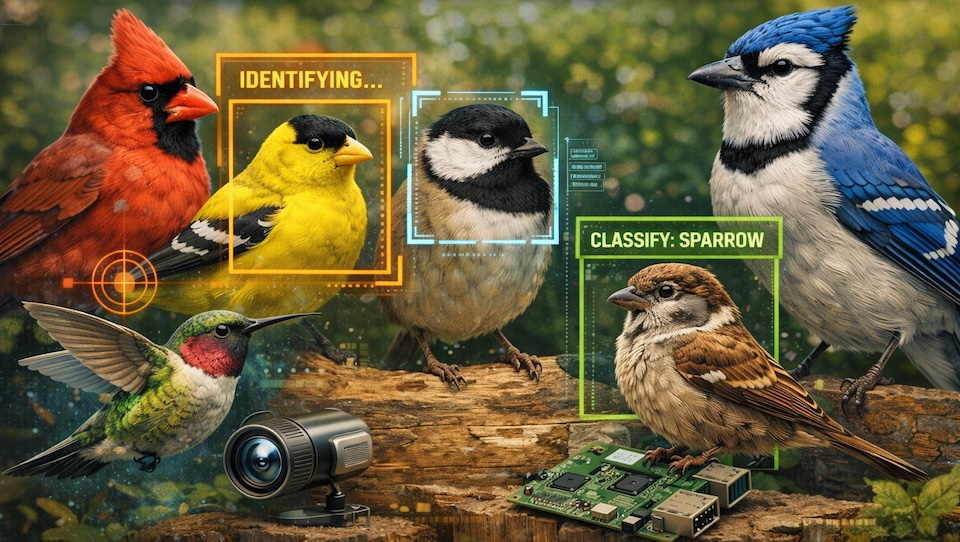

ComputerVision Bird Feeder (part 1)

Computer vision feels like one of those technologies that’s everywhere—self-driving cars, security cameras, wildlife monitoring—but still oddly inaccessible if you’re not a data scientist. This project started as a way to finally cross that gap: not to invent new models, but to understand how existing ones actually behave when you try to use them in a real system.

Image above generated by ChatGPT

My interest in computer vision goes back to Forest Technology Systems, where we built camera systems to help humans detect wildfires. The obvious next step was letting computers do the detecting and having humans confirm the results. It would be faster—and trust me, nothing is more boring than scanning 140 days of “no fire,” followed by suddenly, "fire!". My team at FTS never got there due to other priorities.

Later, at Open Ocean Robotics, I worked alongside a very talented data scientist, Oliver Kirsebom, PhD. He was doing what felt like magic at the time: detecting objects on the horizon and classifying them as boats or navigational aids. Talking with Oliver made me want to learn this tech properly. When I floated a few project ideas, he suggested bird detection—mainly because I wouldn’t need to train a model. There are solid open-source models available, which meant I could focus on using computer vision rather than building it (possibly a future project?).

While Googling around, I found an open-source North American bird classifier on Hugging Face by a user named chriamue. It had decent adoption and seemed like a good place to start.

I dove in with enthusiasm—and immediately ran into reality. I’m not a Python expert. I paused the project and took a LinkedIn Learning Python course aimed at experienced developers. It was well done, but long, and I found myself frustrated re-learning fundamentals when I just wanted to solve a specific problem. Momentum faded.

So I made a snap decision: I’d do it in JavaScript.

Yes, I know—JavaScript isn’t most people’s first choice for machine learning—but I genuinely enjoy Node.js. The switch re-energized me, and by this point ChatGPT was everywhere. I leaned into it hard, using it to “vibe code” pieces I didn’t fully understand yet.

... At first, it felt incredible.

“I have this issue—where should I look?” → “You need to convert the ONNX model to TensorFlow so you can use TensorFlow.js.”

That advice sounded reasonable, but that was the trap. What followed was a cascade of version mismatches, incompatible libraries, and subtle runtime failures. The most maddening issue: when the code did run, it always returned index 9 — an albatross — regardless of the input image. When Thor hit the same problem, he had altered the index, and 9 was the "African Booby", like it was mocking me! This is now a standing joke around the office.

Here’s the first big lesson: vibe coding is great for momentum, but terrible for deep debugging. Because this was a spare-time project, it took me a while to realize ChatGPT was stuck in a loop of the same five suggestions. Each fix felt plausible, but none moved the project forward. Eventually, I shelved it again.

The second lesson came from a random coffee chat at my new job at Starfish Medical. I mentioned the problem to Thor Tronrud, PhD. He pulled the model into Python and immediately got correct results. The ONNX model worked perfectly. He then converted it to TensorFlow — no luck. He trained a brand-new model directly in TensorFlow—still no luck in Node.js. He even retrained it after spotting a potential issue. Same result.

That was the moment the pattern became clear.

The Python eco-system for computer vision is simply more mature, better supported, and easier to reason about than Node.js. Node can work—but you’re swimming upstream, and every abstraction layer costs time and in my case, motivation.

Thor and I made an executive decision: if this project was going to move forward, Node.js had to go.

Back in Python (and back to vibe coding, but with more skepticism), I found a library that let me host a RESTful API. The API I built accepts an image, runs inference, and returns the most likely bird—or an error. Finally, the computer vision model was working as a standalone service running under uvicorn.

I deployed it to a Raspberry Pi Nano, where it runs noticeably slower—but works. The Nano was chosen because of the power consumption. The end goal was to run this on battery with solar power, so it needed to be a small electal footprint. The Nano was a pretty great match for that.

Huge thanks to Oliver and Thor for helping me get this far. In Part 2, I’ll shift gears into the electromechanical side of the project, using a proximity sensor to trigger the camera when a bird arrives.

Stay tuned ...